Monthly Meeting Notes January 6

Another good turn out for the start of the year, thanks for all who attended. We started off with an article from the Hancock Museum Natural History Society about John Hancock: A Biography by T Russell

Goddard (1929). This was suggested by Val who thought it appropriate as we meet in the upstairs cafe the first Wednesday of every month.

If you are interested in John Hancock you can find out more by going to the Natural History Society Of Northumbria or read the article taken from the web site further down this page:

Ancroft

With permission of The Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne

nlhgroup1@gmail.com

Ancroft by Maureen Philips

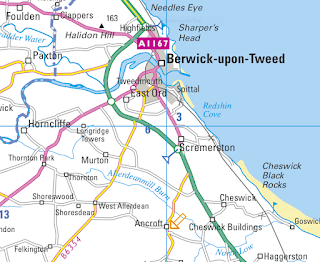

Ancroft is about five and a half miles south of Berwick, there are several suggestions as to how it got its name:- It could be an abridged version of St Aidens Croft. St Aiden was the first Bishop of Lindisfarne (Holy Island).

- Possibly from a church dedicated to St Anne

- Derived from old English word for single or lonely

From the 13th to the 16 th century Ancroft was under constant conflict between Scotland and England due to being so close to the border. People were raided, murdered and dwellings burnt. Fortified towers were built including Ancroft Church Pele Tower. In 1667 the village was almost wiped out by plague and victims were carried out into the fields and their bodied covered with shelters made from branches of broom, a gorse like shrub with yellow flowers that are often habited by Yellow Hammer Birds. After death the bodies and shelters were burned to stop the spread of the infection. The infected area is known as Broomy Hill. The mounds where the village first stood can still be seen and is a protected site of Historical interest.

Within the next century the population increased to over 1000 which included farming workers, miners and boot and clog producers. Marleborough army marched in boots made in Ancroft.The line of trees on the southern skyline is known as "Cobblers Row" and each tree is said to represent a working cobbler.

The church of Saint Anne is well worth a visit. It is one of the four churches built by the monks of Holy Island priory on their mainland esates. In the churchyard there is the headstone marking the grave of eight Poor Clare sisters who escaped from Rouen during the French Revolution and who lived at Haggerston Castle. inside the churchyard gate are some steps known as the "Louping on stane" by which a lady who was going to ride behind a horseman could mount in a dignified manner.

Maureen recommends this site for a trip out and says not to miss the Oxford Team Rooms 1 mile just off the A1 towards Berwick. It is an authenticated farm tee room with good food, jams chutneys and arts and crafts.

If you have any trips you would like to see on these pages bring them along or send them to us.

Local History Quiz

To get our brains going for the new year we spent some time doing a local history quiz. The quiz was from Michael who had given it to us a few years ago. We had two teams and extra points were awarded for more historical information. Everyone contributed and the results strangely enough was a draw. For those of you who could not attend here are the links to the quiz and the answers:

Local History Quiz

Answers to Local History Quiz

Peter has agreed to write the next quiz which will be on general history. I have a wooden spoon for the loosers. Here is an extract from:

Extractor or Universal Repertorium of Literature Science and the Arts Vol 2 March to July 1829 that illustrates the proverb of a wooden spoon:

Next Meeting

The next meeting will be held on Wednesday February 3 in the upstairs cafe at the Hancock Museum at 10:30. Please bring along any work or items of local or general historical interest to discuss. I have been promising to bring along a Devils Toenail for John to see, perhaps I will do it this time.John Hancock: A Biography by T Russell Goddard (1929)

John

Hancock was born in his father’s house at the north end of Tyne Bridge,

Newcastle-upon-Tyne on February 24th, 1808. His love of birds and desire to

collect them appear to have developed very early. We have it on the authority

of his sister Mary that when a little boy of about four years of age he used to

run about the fields at Bensham, where his father had taken a house, trying to

catch the birds. In 1812, after his father’s death, his mother furnished a

house beyond the Windmill Hills, Gateshead, which was then right out in the

open country. Here during the summer months John and Mary Hancock hunted the

fields and hedges for birds, plants and insects. John Hancock first attended

the school of the Misses Prowitt which was situated down an entry off Pilgrim

Street. Later he was sent to the school of Henry Atkinson on the High Bridge,

which at that time was the best in the town.

During

the summer the family used to go to the coast for a period, either to Tynemouth

or Cullercoats and here the children had an opportunity to observe marine

animals and plants. At home in Newcastle during the winter they amused

themselves and their friends with private theatricals, puppet shows, games and

dances. John, we learn, was usually the life and soul of the party and made it

his business to look after the little ones and those who were shy or neglected.

When he

left school he joined his eldest brother Thomas in the saddlery and ironmongery

business at the shop at the end of Tyne Bridge. He soon found business irksome,

however, and longed for freedom to pursue his natural history interests. He

therefore entered into an arrangement with his brother which enabled him to

give up the business altogether. At this time he was collecting birds, insects,

shells and plants and commenced to skin and stuff birds himself. He was on

friendly terms with Richard Wingate, the well-known Newcastle taxidermist, and

spent much time in his workshop. A specimen of the Golden Plover which he

considered his first successful attempt at taxidermy is in the Hancock Museum.

It was mounted before 1829.

As a

young man he thought nothing of leaving home at three o’clock in the morning

and walking to the coast and back, especially at the seasons of the migration

of birds. He was an excellent shot and collected the majority of his specimens

himself. He appears to have been the first to notice the specific distinction

between the Whooper and Bewick’s Swan in January, 1829, but he left it to

others to publish the fact.

As a

young man John Hancock became interested in modelling in clay and casting in

plaster. Several plaster casts of his clay models still decorate the Hancock

Museum, and the two eagles in hardened lead surmounting the stone gate-posts at

the entrance to the museum grounds are also his work. He also executed a number

of wood-engravings. His most successful is a gorged Iceland Falcon which he

engraved in 1845.

His

collecting expedition to Norway with his friends William Hewitson and Benjamin

Johnson in 1833 has already been mentioned in William Hewitson’s biographical

sketch. In 1845 he and William Hewitson went on an expedition to

Switzerland. They travelled up the Rhine to Cologne and John Hancock heard the

nightingale singing for the first time in his life on the banks of this

beautiful river.

He was

keenly interested in falconry and delighted in training peregrines and merlins.

He trained some of his birds on the Newcastle Town Moor.

In 1851

he contributed a series of mounted birds to the Great Exhibition which was held

in Hyde Park, London. Three of the exhibits illustrated different aspects of

falconry and a fourth was a Lämmergeier from Switzerland. These specimens are

still on exhibition in the Bird Room at the Hancock Museum. The exhibits at the

Great Exhibition created a considerable amount of enthusiasm, and John

Hancock’s national reputation as a taxidermist dates from this time. His work

was generally recognised as a distinct advance upon anything of the kind which

had been seen before. In place of the old stereotyped attitudes John Hancock

with great artistic skill had succeeded in creating a semblance of life in his

specimens. He specialised in mounting birds of prey and his collection, now in

the Hancock Museum, is one of the finest in existence of this particular group

of birds.

In 1874

his “Catalogue of the Birds of Northumberland and Durham,” with fourteen

photographic copper plates from drawings by the author, was published as Volume

VI. of the Natural History Transactions of Northumberland and Durham. In

addition to this volume he published twenty papers in the Annals and Magazine

of Natural History, the Transactions of the Tyneside Naturalist’s Field Club

and the Transactions of the Natural History Society of Northumberland, Durham

and Newcastle- upon- Tyne. He also prepared the Synopsis and revised the

nomenclature for the 1847 edition of Bewick’s “British Birds.” His first paper

“Remarks on the Greenland and Iceland Falcons, shewing they are distinct

species” was published in the British Association Report for 1838.

John

Hancock, was one of the original members of the Tyneside Naturalists’ Field

Club and a Vice-President of the Natural History Society. The prominent part he

played in connection with the planning and erection of the new museum building

at Barras Bridge, and his generosity in presenting his extensive and valuable

collections to the Society, have already been dealt with in previous chapters

of this history. At one period of his life he devoted much attention to

landscape gardening and he planned and laid out a number of beautiful gardens

for his friends.

Finally,

a word should be said about his character and temperament. His habits are said

to have been of Spartan simplicity and temperance. He was kind and gentle,

patient and ever ready to take the upmost pains to explain to others problems

in natural history which he had worked out himself. All children and all

animals loved him. He was never tired of teaching the former how to collect and

preserve their specimens and he was ever solicitous of the comfort and welfare

of the latter. A friend of his, now also passed away, once told the author the

following story which casts a clear light upon his character and his

understanding of the feelings of inarticulate animals. He had been spending a

period at Newbiggin on the coast of Northumberland studying and collecting

birds in company with his dog. The time for his return to Newcastle arrived and

he decided to travel by train. This was in the early days of railways. When he

arrived at the station he discovered that the dog was terrified at the

locomotive and showed great reluctance to go anywhere near the train.

John Hancock, therefore, rather than submit his canine friend to a

prolonged period of terror turned his back upon the station and the two of them

walked back to Newcastle together.

On

October 11th, 1890, he died at his house at the end of St. Mary’s Terrace

opposite to the museum at the age of eighty-three years. He was survived by his

sister Mary who had devoted the whole of her life to the comfort and welfare of

her two bachelor brothers.

Reference:-GODDARD,

T R (1929). The History of the Natural History Society of

Northumberland, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne 1829-1929. pp.171-176.